Investigation and arrest

If you are a victim or witness in a serious crime, police will ask you to make a statement about what happened to you, or what you saw or heard, as part of their investigation. They will type up what you say and ask you to read what they have typed, and to sign it. By signing it you are agreeing it is a true account of your experience so be sure to read it carefully first. If you are distressed or in shock when you make your statement and realise later that you forgot to mention something, let the police officer in charge of the matter know as soon as possible, even if you don’t think what you have remembered is important. You can make a second police statement about this new information.

If you are under 16 years of age or have a cognitive impairment, police might make an audio or video recording of their interview with you rather than typing up a written statement.

If you are a victim of domestic violence, you also might not have to make a written statement if police recorded your evidence or statement either at the scene or later.

When they have enough evidence, the police will arrest and charge the person/s they believe responsible for the crime (‘the accused’). They will photograph and fingerprint them, to formally identify them.

Bail

Bail means the temporary release from custody, usually on conditions, of an accused until it is time for their trial. The criteria for granting bail in NSW is set out in the Bail Act 2013.

Police will usually refuse bail when the charges are serious and take the accused to the Local Court, where they can apply again to the magistrate.

The accused will appear before a magistrate in the Local Court, and can apply for bail. If the magistrate refuses bail, the accused can apply again to the Supreme Court.

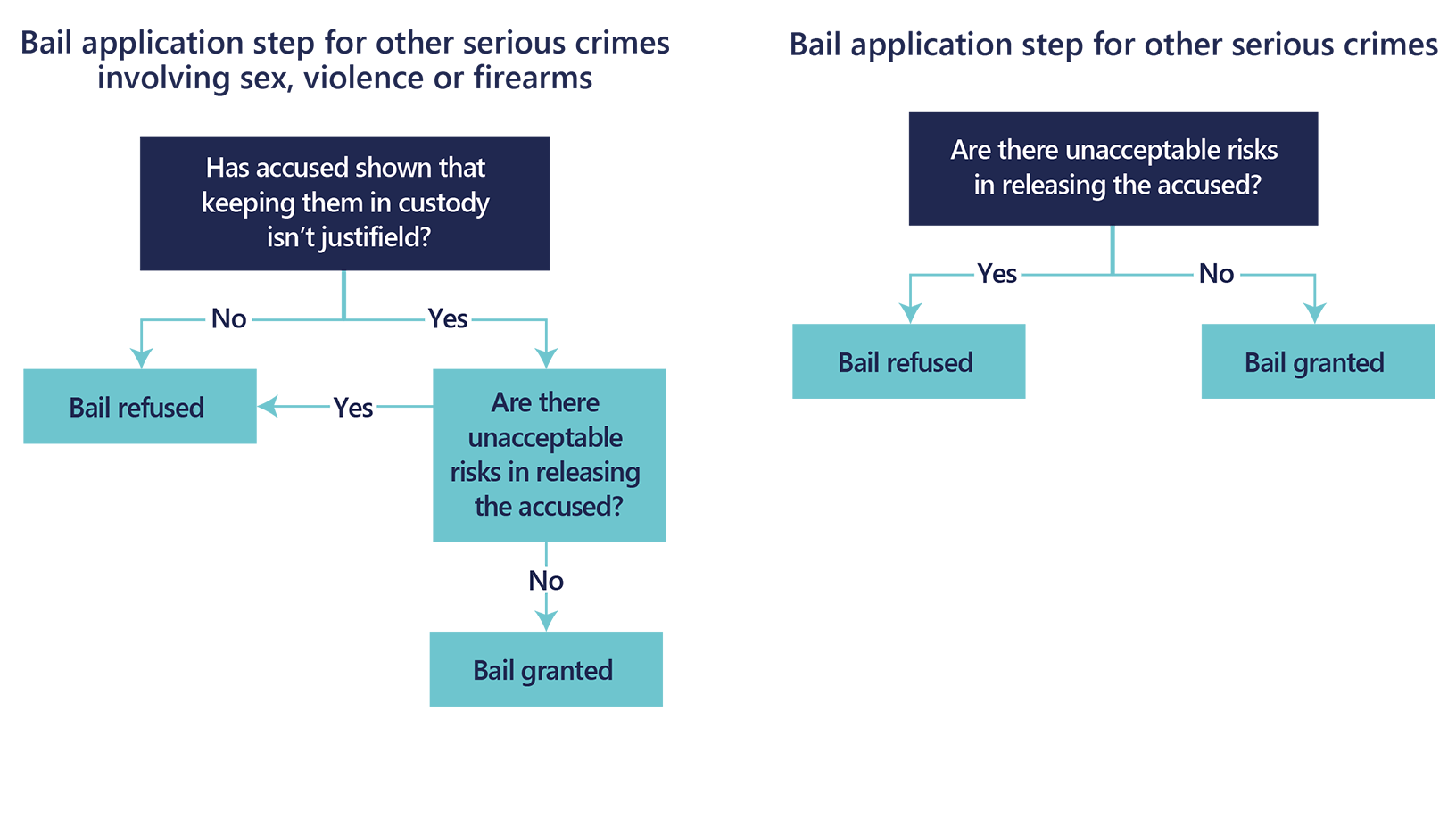

For some serious crimes involving sex, violence or firearms, a bail application has two steps.

First, the accused has to show that keeping them in custody isn’t justified. This is called ‘showing cause’. If the accused isn't successful in ‘showing cause’, the magistrate or judge will refuse bail.

If the accused does show that keeping them in custody isn’t justified, the magistrate or judge will go to the second step in the process. This is to consider whether there are ‘unacceptable risks’ in releasing the accused – that is, risks that they will fail to appear in court, commit a serious crime, threaten someone’s safety, or interfere with witnesses or evidence. If these risks exist, the magistrate or judge will refuse bail, or grant bail with conditions.

If the accused is charged with a crime that doesn’t require them to ‘show cause’, the magistrate or judge will go straight to the second step and consider whether it would be an unacceptable risk to release them.

The court will take into account the views of the victim and their family members when deciding on bail. You will not have to appear in court, but be sure to tell the police officer in charge if you have any fears or other concerns about the accused being released from custody

Bail conditions

Bail conditions the court can impose on the accused to protect victims and witnesses include:

- a curfew, for instance not leaving home a night

- not making contact with victims and witnesses

- not going near victims and witnesses.

Other bail conditions the court can impose to ensure the accused attends court include:

- surrendering their passport

- reporting to police on a regular basis

- depositing a large sum of money that will be forfeited if bail is breached

- living at a certain address

- not drinking alcohol

- attending drug and alcohol courses or rehabilitation

- attending medical appointments.

While the steps for granting bail in the Supreme Court are the same as in the Local Court, Supreme Court bail applications are normally a more formal process, and the accused will usually appear from prison via AVL link rather than in person.

If you are a victim of a serious personal crime, the police or ODPP will contact you if the accused is granted bail.