Most criminal cases will start in the Children’s Court if the accused is a young person. Many will be finalised there, but more serious matters will usually be transferred to the District or Supreme Court, where the young person will be dealt with under the same laws that apply to adults.

In this section of the website, and in the courts, a ‘child’ charged with a criminal offence is referred to as a ‘young person’.

Age of criminal responsibility

In Australia, children under the age of 10 years cannot be charged with a criminal offence.

If they are between 10 and 14 years old, the prosecution has to show that they knew what they were doing was seriously wrong for a case to continue.

If they were under the age of 18 years when the alleged offence occurred and were charged prior to turning 21 years old, they are considered a ‘child’ under the law.

ODPP prosecutes serious crimes

Generally police prosecutors are responsible for prosecuting matters in the Children’s Court. However where the offences involved are more serious crimes, the ODPP will take over the prosecution from police. The ODPP will also take over the prosecution of all sexual offences where the victim is a child.

The ODPP will contact you if you are a victim or another key witness in a matter we take over. We will also usually want to meet you before the matter goes to court to discuss your witness statement, help you feel prepared to give your evidence, and explain what is likely to happen in court on the day you appear (see Going to court and being a witness). If you have a Witness Assistance Service (WAS) officer, they will also help you feel ready to give your evidence. This can include taking you on a tour of a court so you know who the people are and what they do.

The Children's Court – first step in most matters

Most matters involving a young accused person start off in the Children’s Court, where they are asked to plead. (Traffic offences by a person old enough to have a licence are an exception and are dealt with in the Local Court.)

If there is no designated Children’s Court in the area, the Children’s Court will usually sit in a Local Court courthouse.

Unlike other courts, Children’s Court proceedings are not open to the general public. To attend, you have to be directly involved, a family member of someone who died as a result of the crime, or a member of the media.

Media reports cannot identify the young person, although if they are convicted of a very serious offence, the court can allow their name to be published.

Other ways in which the Children’s Court is different from other courts are that proceedings are less formal, and the magistrate will take care to explain to the young person what is happening and to give them the opportunity to be heard.

Next step depends on charges

Whether a matter stays in the Children’s Court or is committed (transferred) to the District or Supreme Court will depend on the charges and the nature of the crime. This is because there are limits on the penalties the Children’s Court can impose, and they may not be severe enough in very serious matters.

Other reasons a Children’s Court magistrate might commit a matter to a higher court include if adults were involved with and charged over the same offence and the Court decides that the young person and the adult should be jointly dealt with in the same higher Court.

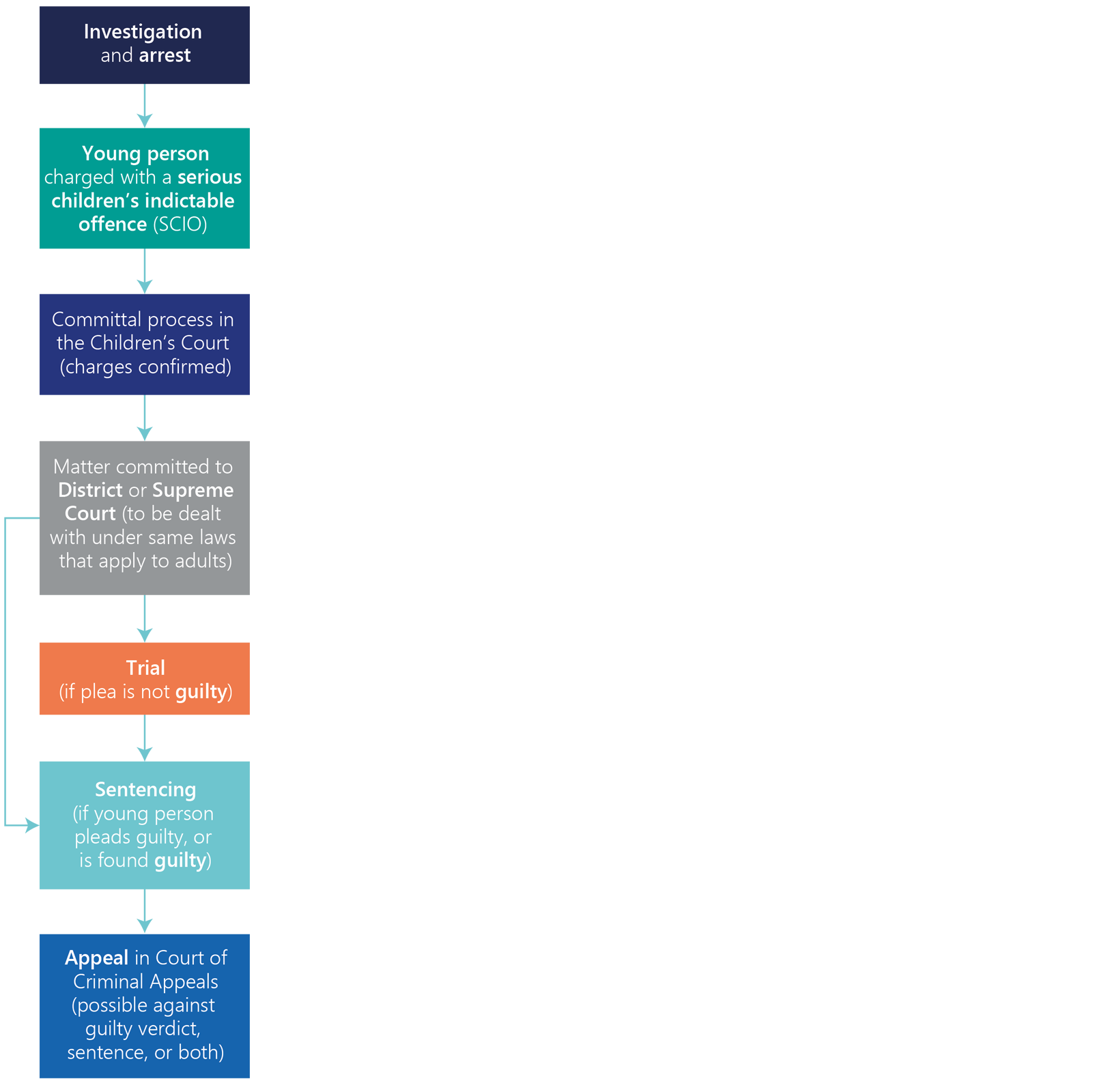

- Serious children’s indictable offences (SCIOs)

Very serious crimes committed by young people are called ‘serious children’s indictable offences’ (SCIOs). They include murder and manslaughter, serious sexual assaults and other crimes of personal violence, armed robberies, firearms offences and some drug offences. The ODPP takes over the prosecution of all these matters from police.

The Children’s Court does not have the power to deal with SCIOs and they are always committed for trial or sentence to the District Court, or to the Supreme Court for the most serious offences (see Matter goes to the District or Supreme Court).

Committal stage

Before this happens, what is called a ‘committal’ process takes place.

This is so the ODPP can examine whether the evidence the police gathered in their investigation is strong enough to support the charges laid, or whether there should be different charges. Once the charges have been settled by the ODPP we file a charge certificate in the Childrens Court. The ODPP and defence then participate in a case conference to negotiate on whether a plea can be obtained. If a plea of guilty is obtained at case conference the matter is committed (transferred) to a higher court for sentence. If a plea is not obtained at case conference, the matter is committed to a higher court for trial. (see Committal process)

Victims and witnesses are rarely called to give evidence at this stage, although it can happen in limited circumstances.

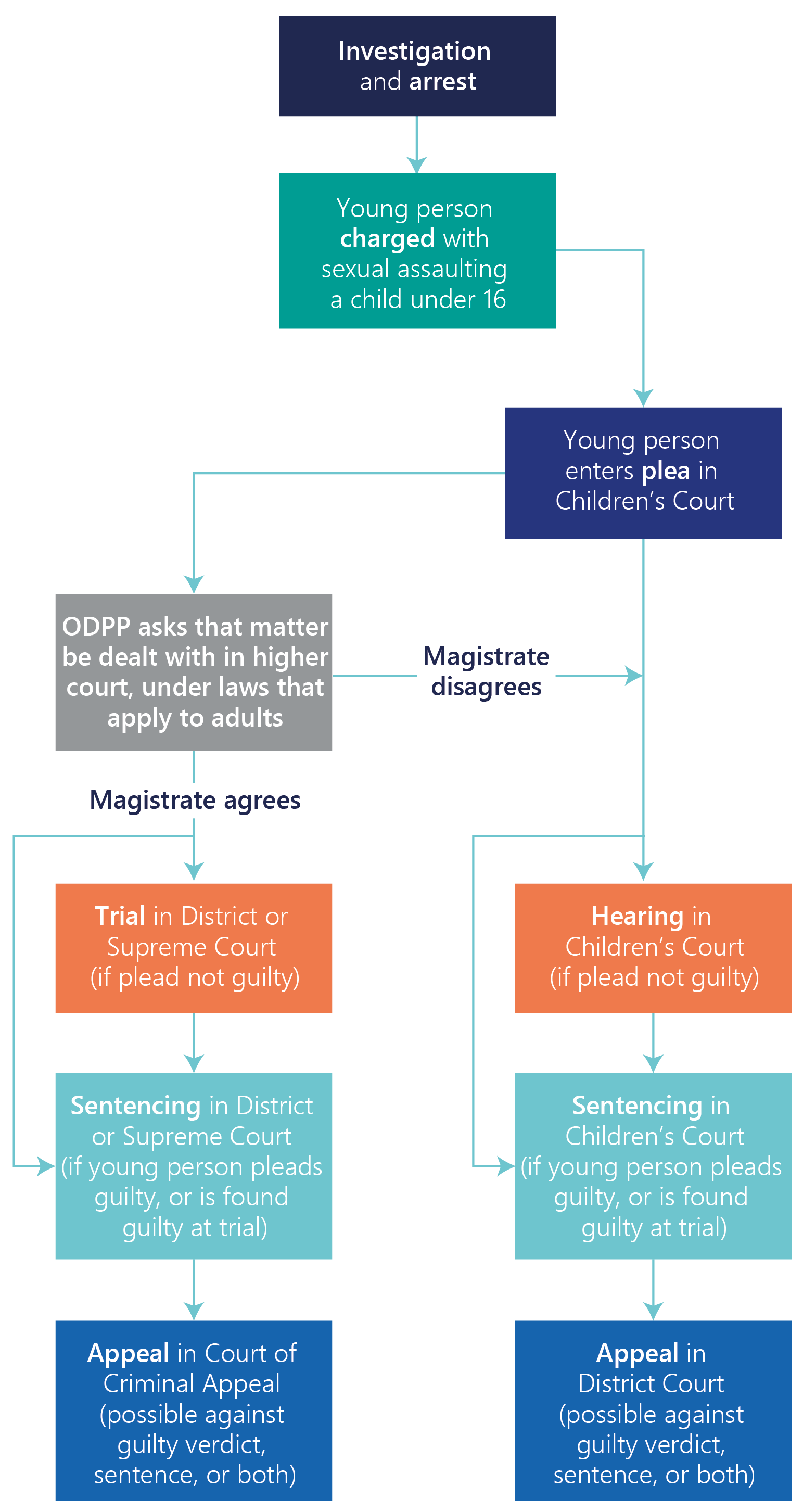

- Child sexual assaults

If a young person has been charged with sexually assaulting a child under 16 but the charge does not fall under a ‘serious children’s indictable offence’ (SCIO), the prosecution of the matter will generally proceed in the Children’s Court. However the ODPP can apply to the magistrate to commit (transfer) the matter to the District Court if we think the crime is serious enough to be dealt with under the laws that apply to adults.

We can make this request whether the young person pleads guilty or not guilty.

To transfer a child sexual assault matter to the District Court, the magistrate has to be satisfied that:

- the evidence is strong enough to convince a jury beyond reasonable doubt that the young person committed the assault and

- the Children’s Court penalties may not be sufficient.

Rather than having witnesses give their evidence in person at this stage, the ODPP will provide written statements to the Children’s Court as the evidence. Victims of sexual assault will only have to give evidence during this early process if the magistrate agrees there are ‘special reasons’ in the interests of justice that they should, and these are difficult to show. Other witnesses can only be called if both the ODPP and the young person agree, or the magistrate is satisfied there are ‘substantial reasons’ in the interests of justice to call them. This is not as difficult as showing there are ‘special reasons’, but it is still a barrier.

The magistrate will consider the evidence in the prosecution case and also determine if the matter is sufficiently serious to be dealt with in the District Court. If the magistrate agrees that the evidence meets the standard and the offence is sufficiently serious, the case is transferred to the District Court for trial.

If the magistrate decides that the evidence is sufficient but the matter is not sufficiently serious, the magistrate will deal with it in the Children’s Court (see Prosecutions in the Children’s Court below)

- Less common paths to the District Court

Less common paths to the District Court for a young accused person include when the charges are serious (indictable) and:

- the young person or the ODPP ask the magistrate for a trial in the District Court or

- the ODPP files charges directly in the District Court.

Even if a young person is committed for trial and is found guilty, or pleads guilty, in the District Court, if they are under 21, the matter can still be returned to the Children’s Court for sentencing in accordance with the penalties available in the Children’s Court. .

Additionally, a District Court judge is also entitled to sentence the young person in accordance with the penalties available in the Children’s Court.

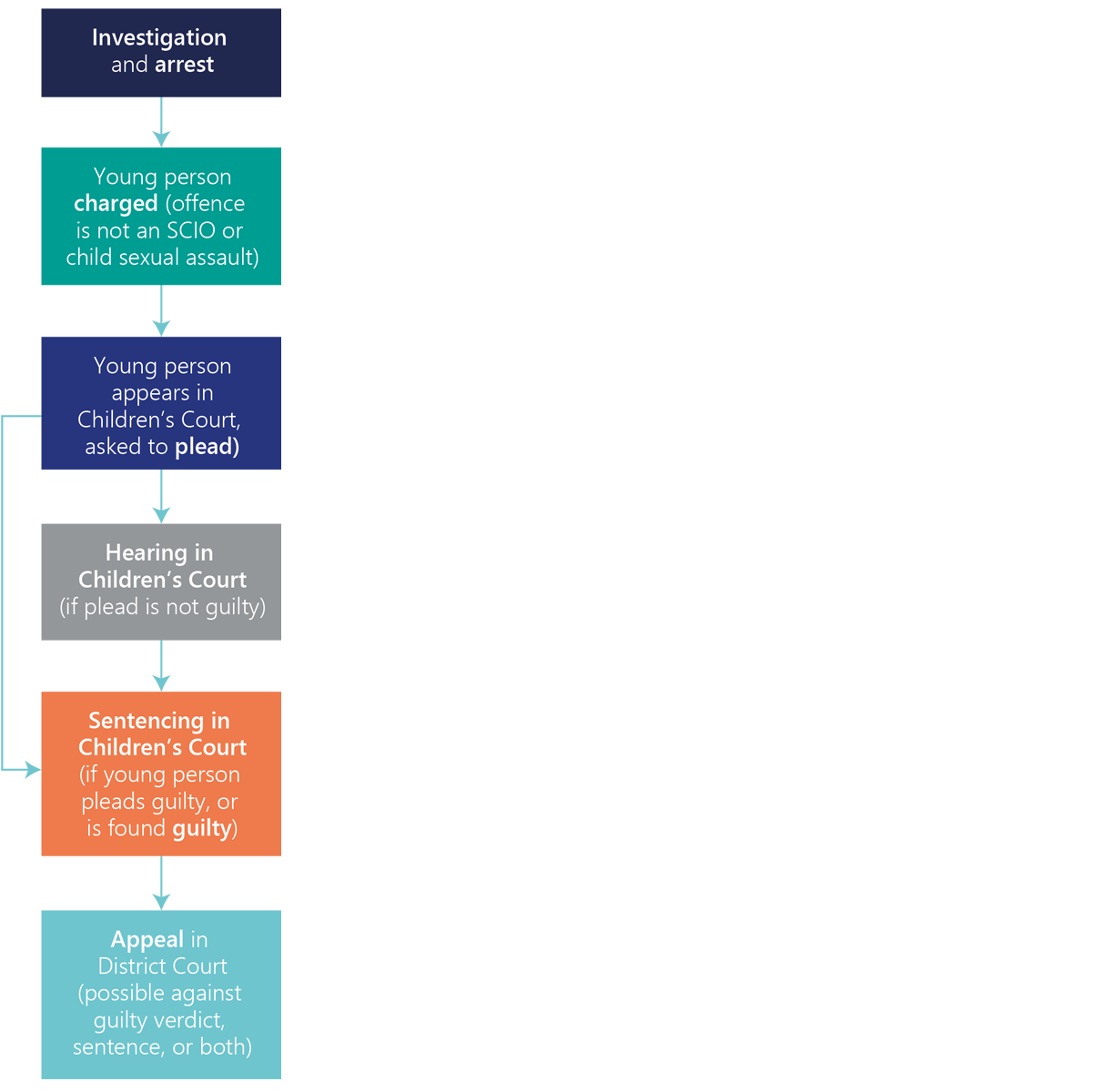

- Prosecutions in the Children’s Court

Most other criminal matters involving a young accused person will stay in the Children’s Court. If the young person pleads not guilty, the magistrate will hold a hearing. The magistrate will determine whether the evidence supports a finding of guilty or not guilty.

For guilty pleas, or if the young person is found guilty, the magistrate will sentence them under the Children’s Court penalty laws.

Young person pleads not guilty

When a young person pleads not guilty, the magistrate will order the prosecution to serve its evidence (called a ‘brief’) within four weeks. A brief will usually include victim and witness statements, results of forensic tests, such as blood alcohol tests, and, if relevant, photos or maps of the scene of the incident.

The court will normally then adjourn for seven weeks so the young person’s lawyer can respond to the brief.

If after the adjournment the young person again pleads not guilty, the matter will be listed for a hearing.

Domestic violence timetable

If the young person is charged with a domestic violence offence, a different process applies so the matter can be dealt with in the fastest possible time.

The prosecution will serve a ‘mini brief’ on the young person and their lawyer no later than the first time the matter is mentioned in court. This will include the alleged facts of the case, a copy of the victim’s statement, and any relevant photos.

The magistrate will usually ask the young person to enter a plea the first time the matter is mentioned in court. If the young person has not had a reasonable chance to look at the mini brief or get legal advice, there will be an adjournment for up to 14 days.

If the young person pleads not guilty, the magistrate will set a hearing date. The prosecution will have to serve the rest of its brief 14 days or more before that date.

Main steps in a Children’s Court hearing

The steps in a hearing in the Children’s Court are very similar to those in the Local Court, although the process is much more informal and the magistrate will spend time explaining to the young person what is happening.

The main steps are:

- the prosecution makes an opening statement about the case (called a ‘submission’)

- the accused’s lawyer (the defence) may also make an opening submission

- the prosecution calls its witnesses

- the first prosecution witness gives his or her evidence-in-chief, then is cross-examined by the defence. The prosecution may then re-examine the witness, and the magistrate may also ask some questions

- the other prosecution witnesses then give their evidence, following the same process (see On the day: Going to court and giving evidence)

- the defence calls its witnesses, who go through the same pattern of evidence-in-chief, cross-examination and re-examination. The young person does not have to give evidence but if they are going to it will be at this point, as a witness for the defence

- the prosecution makes a closing address

- the defence makes a closing address

- the magistrate may adjourn to have more time to consider all the evidence and arguments

- the magistrate announces the verdict

- if it is ‘guilty’, the magistrate will sentence the young person. Sentencing will usually start straight after the verdict, but it may also be delayed so reports / character references can be prepared

- if the verdict is ‘not guilty’, the young person is free to go.

Delays and adjournments

Matters in the Children’s Court will sometimes be delayed or adjourned to another day. This can be upsetting and frustrating when you have spent time preparing to give your evidence and have planned your day around being in court.

Reasons for adjournments can include witnesses not being available; courtrooms not being available; the young person not having a lawyer, or changing their lawyer; the young person needing psychiatric or psychological assessment; the magistrate asking for a Juvenile Justice background report; or the prosecution waiting on crucial evidence.

The ODPP or police will tell you if we find out a matter has been delayed or adjourned, but we do not always know until the day.

Sentencing

If a young person pleads guilty or is found guilty in a Children’s Court matter, the magistrate will sentence them.

A magistrate will generally require a background report on the young person – which Juvenile Justice usually prepares. If one is not on file there will be an adjournment so one can be provided. This normally takes two weeks when the young person is in custody and up to six weeks otherwise.

If the young person pleaded guilty and there has not been a hearing, the lawyers for each side will agree on the facts of the case to provide to the magistrate (called ‘agreed facts’). The defence might also present psychological/psychiatric or medical reports, character references, information on the young person’s ties to the community, any rehabilitation program they may be involved in and, in some cases, an apology letter.

If you are a victim of a sexual or violent offence or are a family member of a victim who died as the result of a crime, you will usually be able to make a victim impact statement (VIS), if you want to. The prosecutor will hand it to the magistrate before the offender is sentenced. You can also choose to read it out, or have someone read it for you. Talk to the prosecutor as early as possible if you want to make a VIS as they can’t be made in all matters (see Victim impact statements).

Once the magistrate has received and heard the sentencing evidence, the magistrate will consider what penalty to impose.

Penalties

The penalties available in the Children’s Court are different to those in other courts, and the court gives more weight to rehabilitation and education than to punishment and deterrence.

The magistrate will also consider the young person’s age, how much their youth contributed to them offending, the circumstances of the crime, and whether and when they pleaded guilty.

The maximum penalty the Children’s Court can impose for any one offence is two years in detention, and, for more than one offence, three years in detention.

Any sentence of detention will be in a Juvenile Justice centre – the Children’s Court cannot send a young offender to prison. Children’s Court detention orders are called ‘control orders’.

Other penalties the Children’s Court can impose include a:

- suspended control order sentence (where a sentence to spend time in custody is suspended and the young person is released into the community on a good behaviour bond)

- community service order

- probation period, which requires a higher level of contact with Juvenile Justice than a good behaviour bond

- fine

- good behaviour bond

- caution, which means the charges are dismissed without conviction

- dismissal of charges, with or without a caution.

If a young person is under 16 and pleads guilty or is found guilty in the Children’s Court, no conviction will be recorded, which means the offence will not form part of their criminal history.

(See Sentencing for more information.)

- District and Supreme Court sentencing

If an offender was under 18 years at the time of the offence and is still under 21 when being sentenced in the District or Supreme Court, the judge can order that some or all the detention period be served as a juvenile offender. After turning 21 years old, an offender cannot serve time as a juvenile unless they are near the end of their non-parole period or their sentence.

A prison sentence for an SCIO cannot be served as a juvenile after the offender turns 18 years old, unless there are special circumstances. These can include that they have a disability, there is an unacceptable risk they will be harmed in prison, or they are near the end of their detention or non-parole period.

- Appeals from the Children's Court

A young person can appeal to the District Court from the Children's Court against their sentence or conviction, or both. The ODPP can appeal if we think a penalty is not severe enough but we cannot appeal against a ‘not guilty’ finding.

Both sides have 28 days to lodge an appeal.

In relation to a sentence appeal, the District Court will either confirm (agree with) the sentence, vary (change) it, or revoke (cancel) it. The District Court can also send the matter back to the Children’s Court. If this happens, the Children’s Court has the same options – it can confirm, vary, or revoke the sentence.

In relation to a conviction appeal, the District Court will consider the evidence from the Children’s Court (by reading a transcript of the evidence) and then determine whether the offender is guilty or not guilty.

- Guiding principles for all matters involving young people

The following principles apply to all courts dealing with a young person:

- ‘children have rights and freedoms before the law equal to those enjoyed by adults, and in particular a right to be heard and a right to participate in the processes that lead to decisions that affect them

- children who commit offences bear responsibility for their actions but because of their state of dependency and immaturity, require guidance and assistance

- it is desirable, whenever possible, to allow the education or employment of a child to proceed without interruption

- it is desirable, whenever possible, to allow a child to reside in his or her own home

- the penalty imposed on a child for an offence should be no greater than that impose on an adult who commits an offence of the same kind

- that it is desirable that children who commit offences be assisted with their reintegration into the community so as to sustain family and community ties

- that it is desirable that children who commit offences accept responsibility for their actions and, wherever possible, make reparation for their actions

- that, subject to the other principles described above, consideration should be given to the effect of any crime on the victim.’