A person is not criminally responsible for an offence if, at the time of carrying out the act constituting the offence, the person had a mental health impairment or a cognitive impairment, or both, that had the effect that the person:

- did not know the nature and quality of the act, or

- did not know that the act was wrong (that is, the person could not reason with a moderate degree of sense and composure about whether the act, as perceived by reasonable people, was wrong).

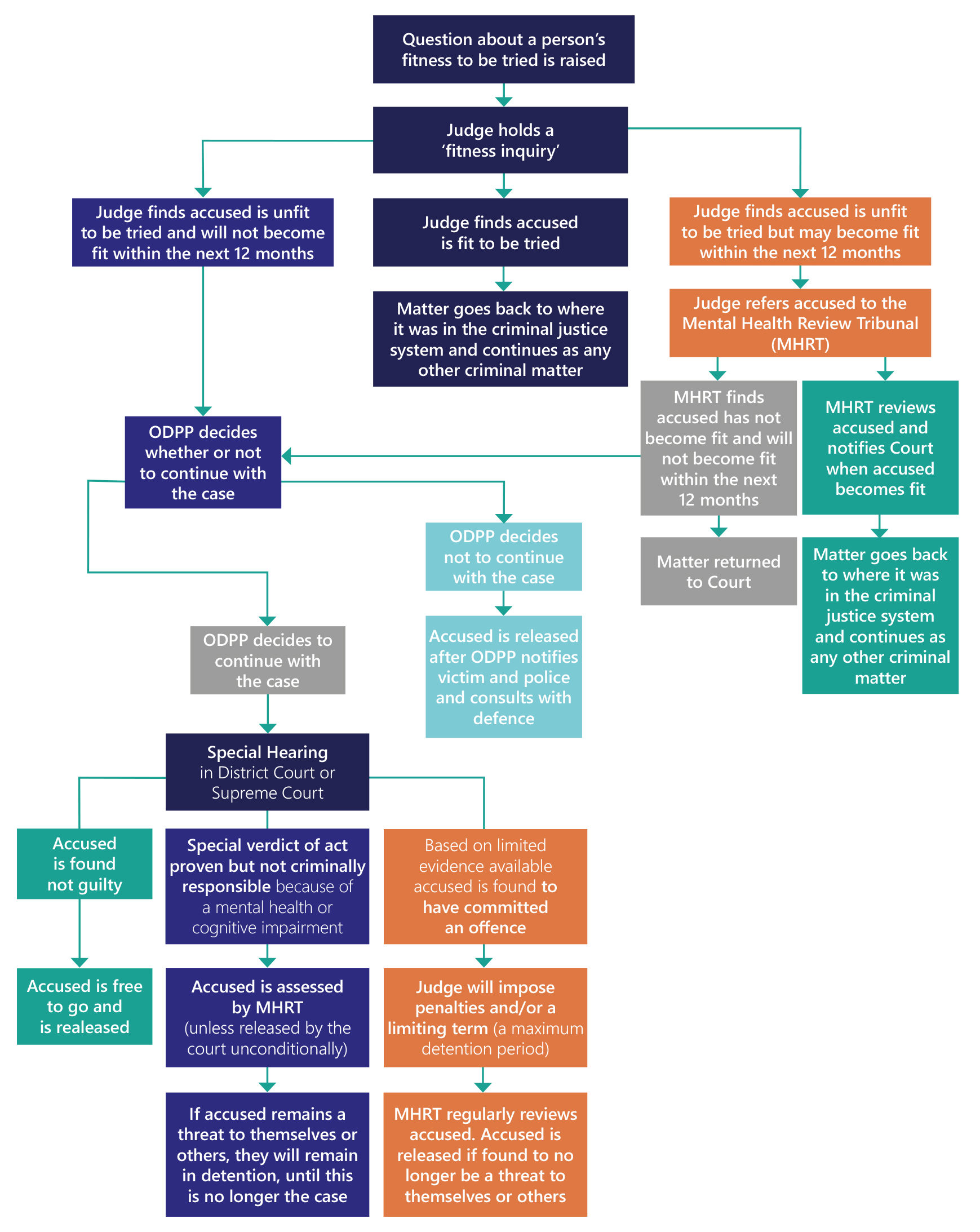

A judge or jury must return a special verdict of “act proven but not criminally responsible” if satisfied that the defence of mental health impairment or cognitive impairment has been established.

In every serious criminal matter, the court will ask for reports on the accused from psychiatrists, psychologists or other medical experts, who will often also be called to give evidence.

It is important to remember that a special verdict of “act proven but not criminally responsible” can have significant consequences. For example, after a special verdict, the court will usually detain the offender and order that they are assessed by the Mental Health Review Tribunal ('MHRT'). The MHRT will not release the person unless and until it is satisfied that they are not a serious risk to others or themselves. The person will remain in detention until this is no longer the case – that is, they will have no minimum or maximum detention period (see Detention for serious crimes involving mental health impairment or cognitive impairment below).

Some defence lawyers avoid using this defence because of the possibility of indefinite detention, and instead ask the court to take the accused’s mental health or cognitive impairment into account during sentencing.

If after a special hearing the MHRT assesses that the accused is no longer a threat, it will usually recommend that they are released with conditions attached, including ongoing treatment and support.

Substantial impairment because of mental health impairment or cognitive impairment

In murder cases, an accused person can be found not guilty of murder but guilty of manslaughter if the court accepts they had a ‘substantial impairment because of mental health impairment or cognitive impairment’ when they committed the offence. This will reduce the maximum penalty that a judge may impose from life to 25 years in prison.

The accused must show that at the time the offence occurred, their capacity to:

- understand events;

- judge whether their actions were right or wrong; or

- control themselves;

was ‘substantially impaired by a mental health impairment or a cognitive impairment’. The impairment has to be from a condition they already had and be substantial enough to reduce murder to manslaughter.