Determining whether a person is fit to tried

If a magistrate or judge accepts that there are genuine questions about whether a person charged with a serious offence is fit to be tried, a judge in the District or Supreme Court will hold what is called a ‘fitness inquiry’.

These inquiries rarely take more than a day. The judge will look at relevant evidence, including psychological, psychiatric and other medical reports. In some matters, the experts who assessed the accused will be called to give evidence. The inquiry will consider whether the accused can understand a trial, instruct lawyers and decide on a defence, among other things. The judge will also consider whether the trial process can be modified, or assistance provided, to facilitate the accused’s understanding and effective participation in the trial.

Questions about ‘fitness’ are usually raised when the accused is still before a magistrate in the Local Court but they can be raised at any time by the prosecution, the accused’s lawyer, or the magistrate or judge.

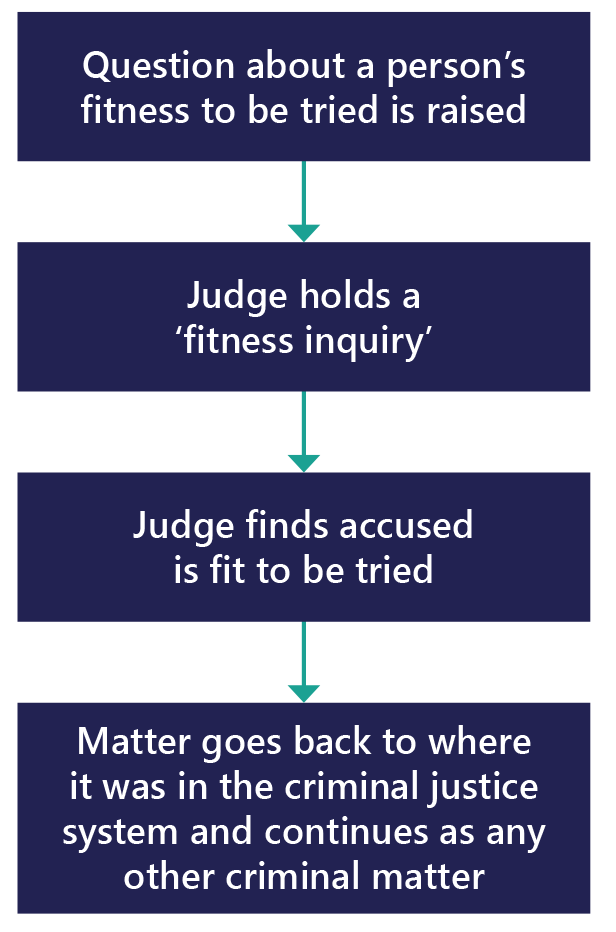

- Judge finds the accused is fit to be tried

If the judge holding the fitness inquiry finds the accused is fit to be tried, the matter will go back to where it was in the criminal justice system and continue like any other criminal matter. For example, if it was at the committal stage in the Local Court, it will return there. If the accused was on trial in the District or Supreme Court, the trial process will continue.

A ‘fit to be tried’ finding does not mean the accused’s mental health impairment or cognitive impairment will not be raised again. During a trial or a sentence hearing, or in a ‘special hearing’ (see ‘Special hearings’ when the accused is unfit to be tried) the court may still hear evidence about the accused’s mental state at the time the offence occurred (see Defence of mental health impairment or cognitive impairment below).

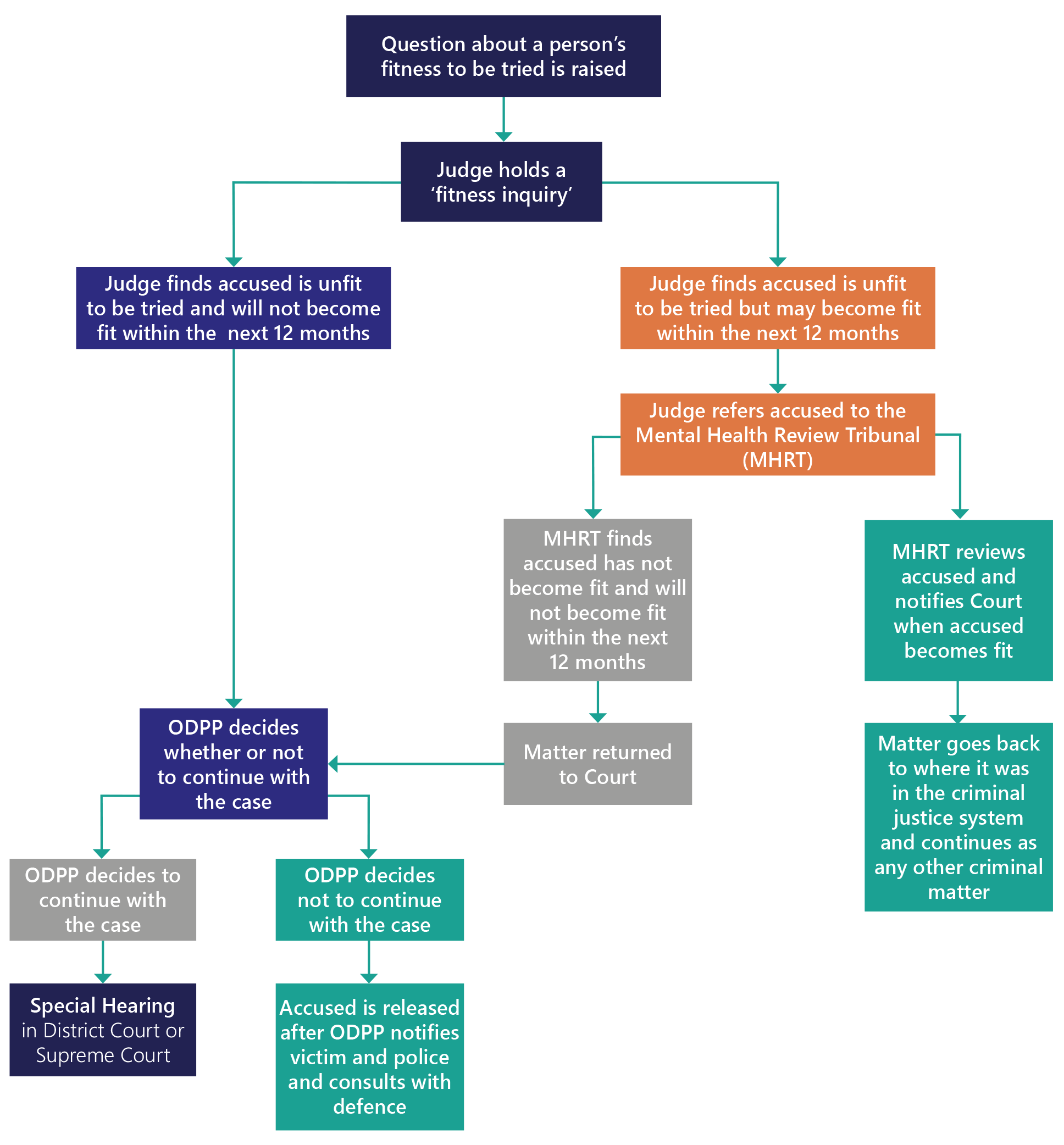

ODPP decision whether to continue with the prosecution

If the court finds the accused will not become fit for trial within 12 months, the ODPP has to decide whether it is appropriate to continue the case, given the accused’s ongoing mental health or cognitive impairment.

If you are the victim, or a family member of a victim who died as the result of a crime, the ODPP prosecutor will talk to you about whether you want the matter to continue, and also consult with the police officer in charge, before making a decision. Other factors that will be taken into account include the public interest, the seriousness of the offence, the accused’s circumstances and criminal history, the time the accused has already spent in detention, and the likely sentence a court will impose.

If, after weighing up all these factors, the ODPP decides not to continue with the case, the accused will be released. The ODPP will notify the victim and the police before this occurs, and will consult with the defence to ensure the accused receives the treatment and care required.

Judge finds that the accused may become fit to be tried in the future

If the judge decides that the accused is currently unfit to be tried but may become fit to be tried within the next 12 months, the judge must refer the accused to the Mental Health Review Tribunal (MHRT) for review. The MHRT is a panel of mental health experts who will review the accused’s fitness to be tried. A person could become ‘fit’, for example, if they had stopped taking medication for a condition such as schizophrenia and begin taking it again.

The MHRT will notify the court when an accused becomes fit to be tried for an offence and the matter will then go back to the criminal justice system and continue like any other criminal matter. The MHRT will also notify the court if an accused will not, during the period of 12 months after the finding of unfitness by the court, become fit to be tried for the offence. The matter will then return to the court and proceed to a special hearing (subject to a decision of the ODPP as to whether or not further proceedings will be taken, as discussed above).

- Judge finds the accused is unfit to be tried

If the accused is found unfit to be tried, the judge must also determine whether the accused might become fit to be tried within the next 12 months. If, following the fitness inquiry, the judge decides that the accused is unfit to be tried and unlikely to become ‘fit’ within the next 12 months, the accused must be tried as soon as possible in a special hearing (subject to a decision of the ODPP as to whether or not further proceedings will be taken).

- 'Special hearings’ when the accused is unfit to be tried

If the ODPP decides to continue prosecuting a case after the accused has been found unfit to be tried, the matter will go to the District or Supreme Court for what is called a ‘special hearing’.

A special hearing is usually before a judge only. It is conducted as closely as possible to a normal criminal trial but the judge can make adjustments to help the accused take part more fully – for example, by having extra breaks if the accused has dementia.This is the stage at which victims and other witnesses are likely to be called to give evidence. To help you feel prepared, the ODPP prosecutor will arrange to speak with you before the hearing date about your police statement and what to expect on the day. If you have a WAS officer, they will also contact you and can arrange a support person to go to court with you when you give your evidence. (See Going to court and being a witness for information on what will happen before you go to court and on the day.)

The verdicts available in a special hearing are different to those in a normal trial. The accused can be found:

- not guilty (meaning they are free to go)

- to have committed an offence, based on the limited evidence available. (The wording of this verdict recognises that the accused may not have been fully capable of giving their version of events to the court)

- to have committed an offence available as an alternative to the offence charged, based on the limited evidence available.

The court can also find that the act was proven but the accused was not criminally responsible because of a mental health impairment or cognitive impairment. This is a special verdict of “act proven but not criminally responsible” that is available when an accused raises the defence of mental health impairment or cognitive impairment.

- Court finds accused committed an offence

If the accused is found to have committed an offence (based on the limited evidence available) the judge will impose the same penalty the accused would have received if found guilty in a normal criminal trial. If that would have included prison, the maximum prison term the judge would have imposed becomes the maximum time the accused can be detained anywhere. It is called a ‘limiting term’. The judge does not impose a non-parole period.

The MHRT will then assess the accused and recommend whether they should be detained in a mental health facility for treatment (which the accused has to agree to) or in prison. The court rarely grants bail while waiting for the MHRT’s assessment if the offence was serious.

During the limiting term, the MHRT will continue to review the accused. If it finds the accused has become ‘fit’, the ODPP may decide to continue prosecuting the case as a normal criminal matter and the accused may face a normal criminal trial.

While the ‘limiting term’ is a maximum detention period, if the MHRT finds a person who is due for release remains a risk to themselves or others, it can make them an involuntary mental health patient, or the Minister responsible for the legislation can make an application to the Supreme Court to extend the limiting term.

- Court finds “act proven but not criminally responsible”

If, after a special hearing, the court finds that the act is proven but the accused is not criminally responsible a similar process applies as when a court delivers a guilty verdict in a normal criminal trial. The court will consider whether a sentence of imprisonment should be imposed or whether a non custodial sentence is appropriate.