An accused person will be sentenced after pleading guilty to a crime or after being found guilty by a magistrate, judge or jury. As they have been convicted, they will be referred to in court as ‘the offender’.

The judge or magistrate will take many factors into account when deciding on a sentence.

Juries don’t sit in sentence hearings.

If the verdict is ‘guilty’, the judge will sentence the offender — usually on another day.

The judge does not usually sentence the accused (now referred to as the ‘offender’, as they have been convicted) immediately after the verdict, but sets a date for a sentence hearing.

- Which court and when?

Sentencing after a guilty plea

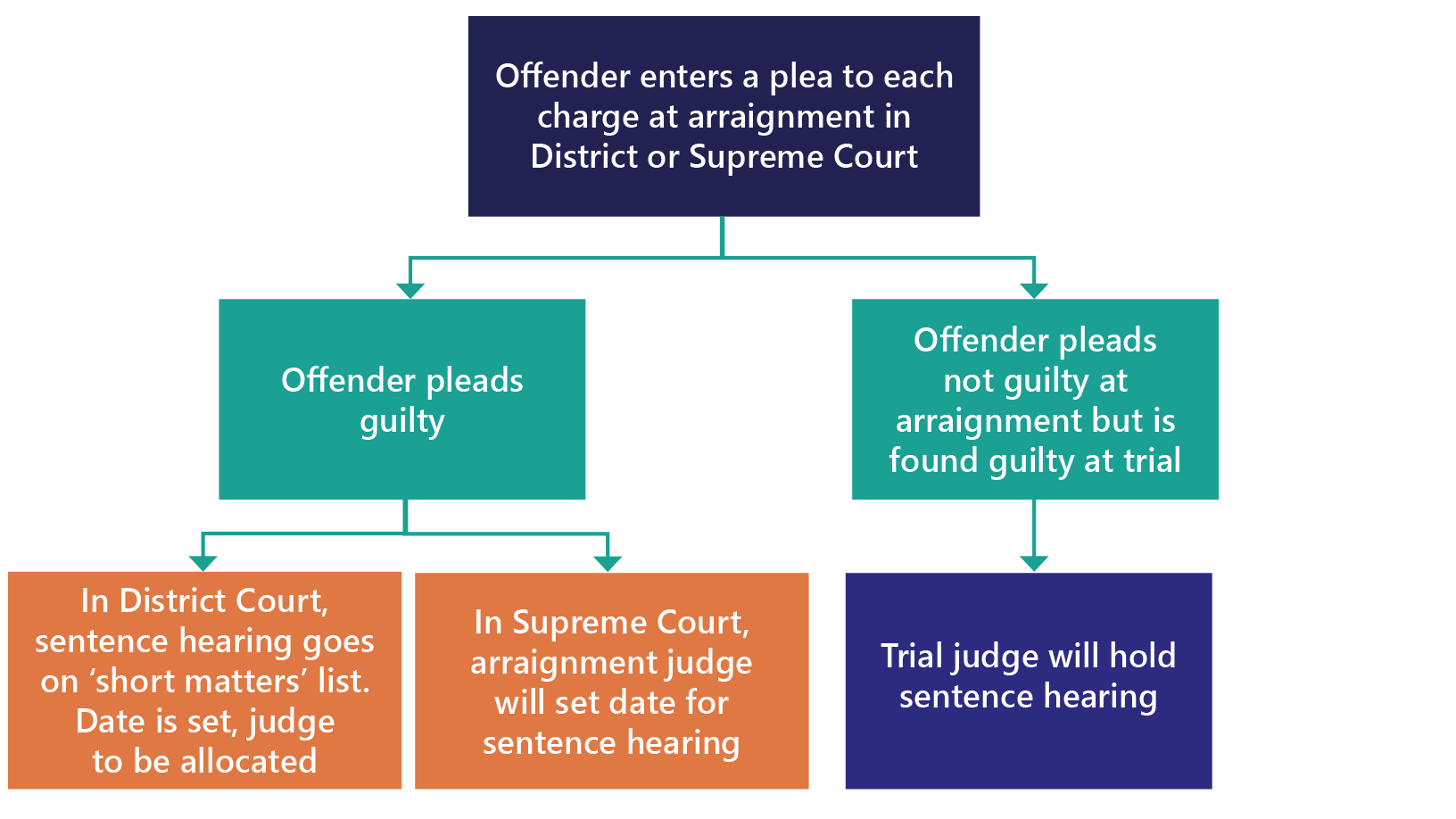

If the offender pleaded guilty to a serious offence, they will be sentenced in the District Court, or in the Supreme Court for the most serious crimes, such as manslaughter and murder.

The first time they appear, each charge will be read out to them and they will be again asked to plead. (This is called an ‘arraignment’).

If the offender is appearing in the District Court and again pleads guilty, their sentence hearing will go on a list of what are called ‘short matters’, and the date for it set. The ODPP will usually not know the judge at this stage; it will be the judge allocated to hear short matters on that date.

There are typically many short matters listed for a day, and delays and adjournments are common. If a matter is adjourned before the judge begins hearing it, it will be put back on the list and given a new date – which can also mean a new judge.

The ODPP will tell victims if we find out early that a sentence hearing has been delayed or adjourned, but sometimes we won’t know until the day before, or on the day.

In the Supreme Court, arraignments are held in Sydney on the first Friday of each month. Usually, the arraignment judge will handle the matter from then on. If the offender again pleads guilty, the judge will set the date for the sentence hearing.

Sentencing after a trial

If the offender was found guilty after a District or Supreme Court trial, the trial judge will sentence them. The sentence hearing will sometimes be on the day the verdict is handed down, but it is more likely to be later. If it is later, it could also be in a different courtroom or courthouse – it will depend on where the judge is sitting at the time.

(For sentencing in the Local Court, see Prosecutions in the Local Court.)

- What happens at a sentence hearing?

At a sentence hearing in the District or Supreme Court, the ODPP prosecutor ('the prosecution' or 'the Crown') will hand the judge all the relevant police, court and other documents, including the offender’s criminal record, if they have one. If the offender pleaded guilty and there was no trial, these documents will include the ‘facts’ of the case, which the prosecution and the defence will have agreed on earlier.

Making a Victim Impact Statement

If you are making a Victim Impact Statement (VIS), the prosecutor will hand it to the judge or, if you want to, you can read it aloud to the court, or have someone read it for you. This is a very important part of the criminal justice process for many victims of crime, but it can be daunting and overwhelming. If you are making a VIS, have someone come to court with you on the day to support you. If you have a WAS officer, they can be there with you.

Talk to the prosecutor as early as possible if you want to make a VIS as they aren't available in all matters.

Reports and references

The defence then usually provides the court with written reports or statements about the offender, such as character references, psychiatric or psychological reports, or medical reports. In some hearings, those character / expert witnesses will also give evidence in person. In serious criminal matters the offender will usually give evidence themselves. The defence lawyer will ask them questions about factors that might affect the severity of the sentence, such as about their background and upbringing; remorse they may feel; any rehabilitation they have started; and whether they have support from family and friends. The prosecution can cross-examine any witnesses the defence calls.

The prosecution and the defence will then make submissions. The prosecution will normally provide information on sentences given for similar offences, and to co-offenders, if there were any.

The judge will often have ordered a pre-sentence report to get more information on the offender’s background and on sentencing and treatment options, if a non-custodial sentence is likely. If the offender is a young person, the report will usually be prepared by Juvenile Justice.

- Are witnesses ever called to give evidence?

Witnesses are rarely called to give evidence in sentence hearings. An exception is if the accused pleaded guilty and the prosecution and defence didn’t agree on all the facts of the case to provide to the sentencing judge. If this happens, the ODPP prosecutor might ask a witness to give evidence on what are called the ‘disputed facts’ only.

For example, if an offender pleaded guilty to an armed robbery and agreed they had a knife but disagreed with the victim’s allegation that they also had an iron bar, the ODPP prosecutor might call the victim to give evidence on this point only. The defence can cross-examine any witnesses the prosecution calls, just as the prosecution can cross-examine any defence witnesses

- How does the court decide on a sentence?

The judge or magistrate will weigh up many factors before sentencing the offender. It is a complex process; there is no ‘formula’ to apply. Many of the things the courts take into account can’t be easily measured, such as the level of harm caused, or how much the offender’s disadvantaged background contributed to them offending. Some factors, such as punishment and rehabilitation, can compete against each other.

The main things the judge will consider are:

- the nature and seriousness of the crime. (If you are in court, you might hear the lawyers and the judge or magistrate discussing ‘low range’, ‘mid-range’ and ‘worst case’ matters. This is to help rank the seriousness of the offender’s crimes against others that are similar)

- the offender’s background, personal circumstances (such as their age, and mental health or capacity) and criminal history

- sentencing laws, and the sentences the courts have given in similar cases.

The judge or magistrate will also take into account:

- the purpose of sentencing, which under NSW law includes to: punish and help rehabilitate the offender; deter them and others from committing similar crimes; and recognise the harm done to the victim and the community

- whether there are what are called aggravating factors, which can increase the seriousness of the crime and therefore the severity of a sentence, or mitigating factors, which can reduce them

- the principles of sentencing, which include that the punishment should fit the crime; prison should be a last resort; and the total sentence should reflect the total criminality of the offences.

The judge or magistrate will also take into account victim impact statements given, or read aloud, to the court. (Family members have to go through an extra step for their statements to be taken into account during sentencing – see Victim Impact Statements).

- Sentences the courts can give

Sentences the NSW courts can give for serious criminal offences include:

- prison

- fines

- orders to pay compensation to the victim

- community-based sentences

- compulsory treatment

- bans on associating with certain people or attending certain places.

Changes to community-based sentencing in NSW took effect in September 2018 and there are now three orders available to the courts. These are:

- intensive correction orders (ICOs), which can include the most serious conditions after prison. An offender who receives an ICO is supervised in the community by community corrections officers and has to comply with at least one other condition. This can include home detention, electronic monitoring, curfews, or community service work. ICOs are available for offenders sentenced to up to two years in prison for a single offence, or up to three years for multiple offences

- community correction orders (CCOs), which can be imposed for up to three years. The courts can include conditions such as curfews, community service work and drug and alcohol bans

- conditional release orders (CROs), which can be imposed for up to two years. These are for crimes at the lower level of seriousness and the courts can impose them with or without recording a conviction against the offender. Conditions can include supervision and participation in programs.

If the offender has been convicted of a domestic violence offence, the courts have to consider the victim’s safety before making a CRO or a CCO. An ICO can only be imposed if the court is satisfied the victim will be adequately protected.

- Maximum penalties

There is a maximum penalty the courts can impose for each crime for which the offender was convicted. For example, the maximum penalty for murder is life imprisonment; for causing grievous bodily harm it is two years imprisonment. Maximum penalties are for the worst cases in a category.

- Mandatory sentences

Two offences in NSW have what are called ‘mandatory sentences’, which means NSW parliament has set the sentence the judge has to impose. The offence of killing a police officer has a mandatory life sentence; assault causing death while drunk has a mandatory minimum sentence of eight years in prison.

- Cumulative and concurrent sentences

If the offender has been convicted of more than one offence, the judge might give them a separate sentence for each. If the judge orders that these sentences are to be served ‘concurrently’, it means at the same time; ‘cumulatively’ means one after another. For example, if the offender receives a two-year prison term for one offence and five years for another, to be served concurrently, the total prison term is five years. If the sentences have to be served cumulatively, the total prison term is seven years.

The court can impose a total maximum sentence when sentencing an offender for more than one offence.

- Form 1 offences

Form 1 offences are offences the offender has been charged with and admitted to but not yet prosecuted for. The judge can take these offences into account during sentencing, so another court case isn’t required to deal with them. For example, if the offender was convicted of four counts of break and enter and steal and had also been charged with the less serious charges of attempt break and enter and malicious damage, the judge can take the less serious charges into account during sentencing.

- Non-parole periods

A non-parole period is the minimum prison term an offender will serve before being eligible to be released on parole. Some offences have a set (called a ‘standard’) non-parole period the judge or magistrate has to impose if the offender is found guilty after a trial.

The court can refuse to set a non-parole period for reasons including the crime was very serious, or the offender has a long criminal history.

- Discounts for early guilty pleas

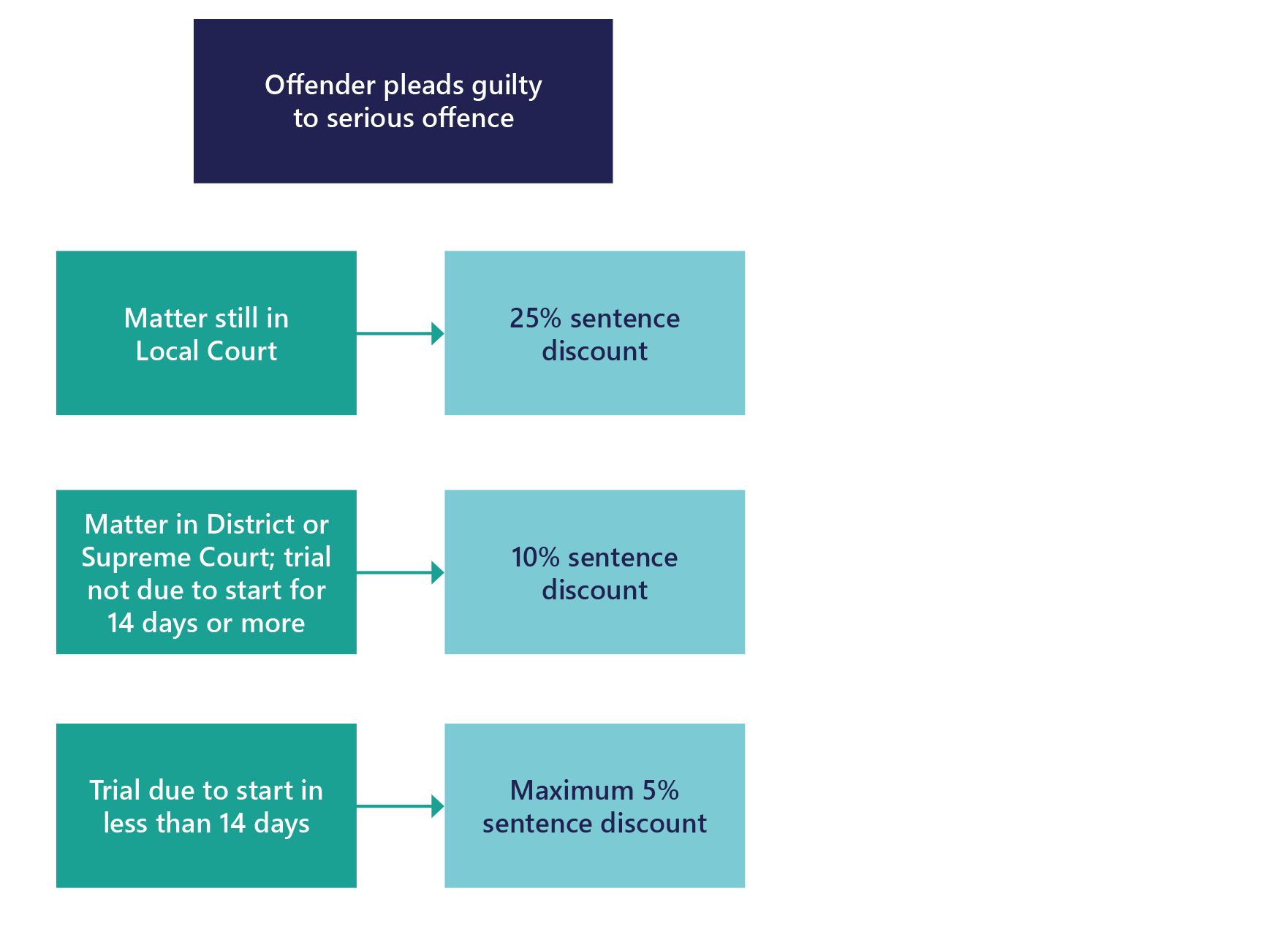

If the offender was charged with a serious offence on or after April 30 2018 and pleaded guilty while the matter was still at the committal stage in the Local Court, they will be entitled to the maximum discount on their sentence available, which is 25 per cent. If the offender pleaded guilty after the matter was transferred to the District or Supreme Court but 14 days or more before their trial was due to start, they will be entitled to a 10 per cent sentence discount. After that, the maximum discount they can get for pleading guilty is five per cent. These discounts are not available for life sentences and judges can decide not to give discounts — or to give less of a discount — in cases of extreme culpability.

If the offender was charged with a serious offence before April 30 2018, the judge will still take an early guilty plea into account during sentencing, but the compulsory discounts tied to the timing of the plea won’t apply.

Why sentences are discounted for early guilty pleas

Sentence discounts are given for early guilty pleas to encourage offenders who intend to plead guilty to do so early on in the prosecution process. An early guilty plea means victims and other witnesses won’t have the stress and potential trauma of having to give evidence, and that the legal process will be over more quickly. Benefits to the criminal justice system include that prosecution and defence lawyers don’t spend time preparing for trials that don’t take place, police can spend more time on frontline work, and there are less matters on court lists waiting to be heard.

- More information

For more information on sentencing in NSW, see the Sentencing information package produced by Victims Services.